GMO’s, Cloning and Synthetic Varieties

When we hear the terms “cloned” and “synthetic” as it relates to plant breeding, does that mean a variety is genetically modified? Recently, a farmer asked a very similar question regarding our Persist orchardgrass. This organic farmer was concerned about planting GMO crops. It’s a good question, so we asked the breeder of Persist, Dr. Bob Conger to help us define these terms. Here’s what he had to say:

“Persist orchardgrass was developed by conventional breeding techniques that have been used for both grass and legume forage crops for many years. In the text Methods of Plant Breeding by H. K. Hayes, F. R. Immer, and D. C. Smith, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1955, they define:

Clone – ‘All individuals derived by vegetative propagation from a single original individual.’ For Persist we selected six outstanding individual plants, divided and repotted (cloned) them to 100 plants of each. Potato is an example of a cloned crop that we eat. It is not planted by seed, but by pieces of tuber (vegetative propagation). Many other crops, especially fruits, are also multiplied by vegetative propagation (cloning).

Synthetic Variety – ‘A term used particularly with cross-pollinated plants to refer to a variety produced by the combination of selected lines of plants and subsequent pollination.’ Another term would be polycross. Generally, grasses are wind pollinated and legumes are insect pollinated.

In the book Grass Varieties in the United States, CRC Press, 1995, the terms ‘clone(s)’and ‘synthetic’ are used in the description of many varieties (especially cool season grasses). For example, Benchmark orchardgrass is a 12 clone synthetic; Haymate is an 8 clone synthetic; Jubilee bromegrass is a 3 clone synthetic, etc. None of the 6 clones of Persist were multiplied in a Petri dish. However, this procedure should not alter the genotype (genetic makeup).

In the strict sense, many, if not most, of the plants we consume have been genetically modified and are GMO’s. For example, genes for disease resistance, adaptation to drought etc., from the wild species of Tripsicum and Teosinte have been bred into corn by conventional techniques. Thus, corn has been genetically modified by cross-pollination with wild relatives. The same hybridization techniques have been used for wheat, soybean, and other crops. If (the farmer) is referring to transgenic plants, i.e., genes inserted by molecular and/or cell culture techniques, there are, as far as I know, no forage grasses varieties that have genes inserted by “molecular and/or cell culture techniques.”

B. V. Conger, Professor Emeritus University of Tennessee and Breeder of Persist Orchardgrass

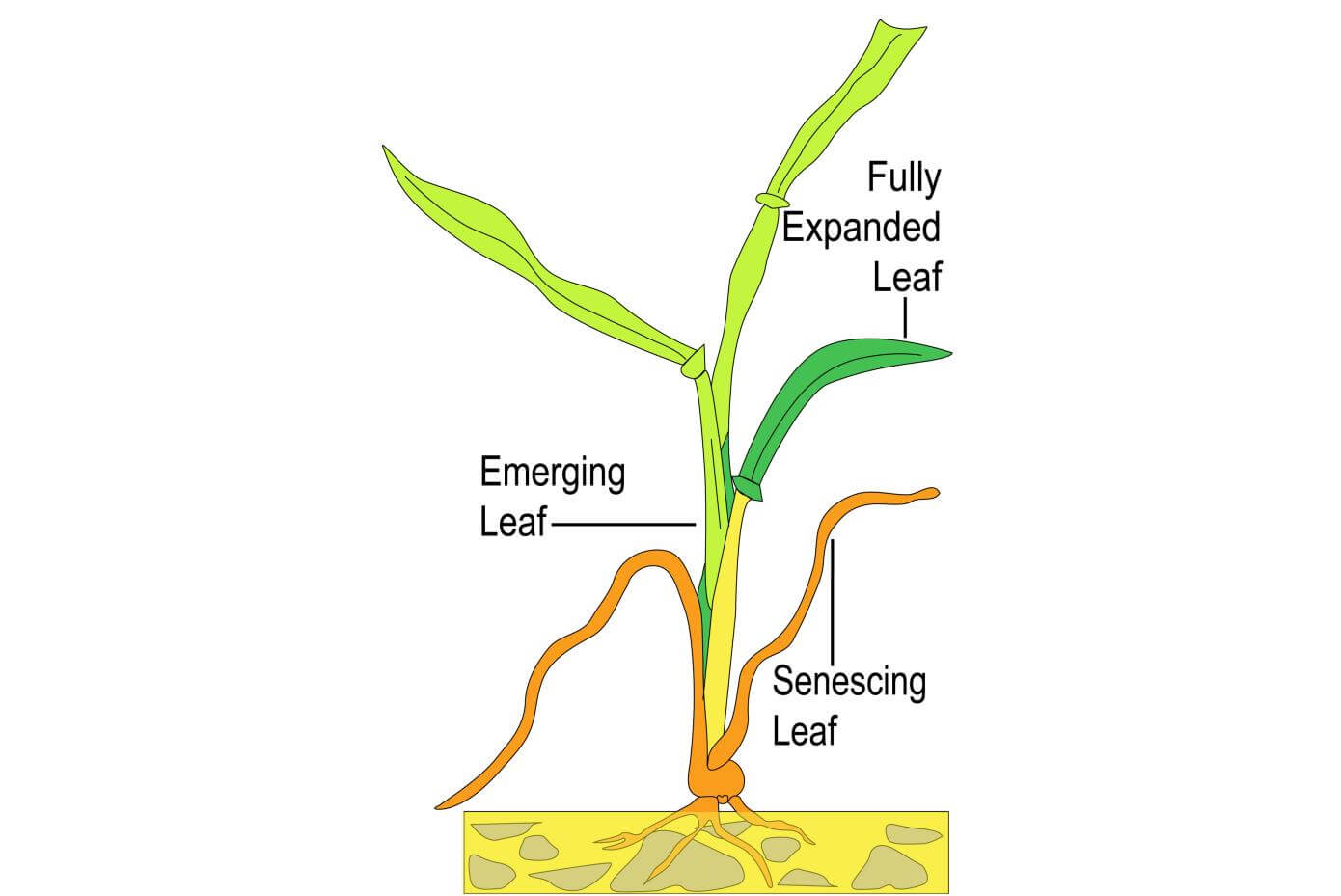

How Grass Grows Part 4: Leaf Formation

“Each crown contains 3-5 miniature (undeveloped) leaves near the apical meristem. Leaf formation proceeds in an ordered fashion with the second leaf growing throught the coleoptile and emerging from within the fold (or roll) of the first leaf. Each succeeding leaf develops from the crown and upwared within the older leaves. Each succeeding leaf is higher up on the shoot than the previous leaf.”

VA Tech’s How Grass Grow’s interactive presentation. See the full presentation under our Resource section at www.SmithSeed.com.